Once Upon A Life

I was in a year-abroad programme, one of 240 American students attending Loyola University's Rome Center in Italy. The school year was winding down. I went out to dinner with a group of friends in Trastevere. After several courses and many bottles of wine we went to a bar, and listened to a singer do jazz standards.

Around 11.30pm Steve Pappas, a friend from Vallejo, California, and I decided to peel off from the group and take a cab across town to Harry's Bar, an old Hemingway haunt on Via Veneto where we'd sit outside, drink whisky and talk to the prostitutes, beautiful women who walked down from the park, Villa Borghese, looking for a rich guy staying at one of the expensive hotels.

We left the bar and I saw a taxi on the other side of the piazza under a full moon. I walked to it and I got in the back and closed my eyes, feeling the effects of many drinks. I heard the front door open and close, looked and saw Pappas grinning in the driver's seat. "We're going to Harry's."

I thought he was kidding. But then I heard the engine start, saw him slip the shifter in gear, and we did a couple doughnuts in the middle of the piazza, tyres squealing, and pulled out, turning right on to a street heading for the Tiber River.

I said: "Are you out of your mind?"

He looked at me in the rear-view mirror and laughed.

Minutes later, negotiating the narrow cobblestone streets of Trastevere, we passed a Carabinieri (national police) sedan parked on the side of the road. I could see the cops look at us in what seemed like slow motion. The next thing I remember, the taxi came to a stop. Unlikely as it was, we were stuck in a traffic jam on the backstreets of Rome. I got out of the taxi and started to run, made it to the Tiber, but hesitated. Instead of going over the wall and climbing the ladder to the riverbank, I crouched behind a car in a small parking lot and waited. I could feel my heart banging in my chest. A few minutes passed and nothing happened. Just as I started to relax, I saw a Carabinieri patrolman appear out of the darkness, coming toward me, gun drawn, shouting something in Italian.

There was nowhere to go. I stood with my arms raised, hands over my head. I was handcuffed and taken to Carabinieri headquarters. Pappas had also been picked up, and we were reunited in an interrogation room and later were questioned by an angry Carabinieri officer.

"Who are you?" We gave him our names. I said: "We're Americans, students at Loyola University."

He didn't seem impressed.

"Why did you steal the taxi?"

"We had too much to drink," Pappas said. "It was a prank."

"This is how a man makes his living and you dismiss it as something trivial, unimportant. You drink too much and use this as an excuse." The Carabinieri officer paused. "In Italy you are guilty until proven innocent." With that, he walked out of the room.

From there I was handcuffed and pushed into the back of a Fiat sedan, flanked by two heavyset cops and driven to the outskirts of Rome. I could see the walls and towers of a prison in the distance set behind a high fence topped with razor wire. I said to the cop on my right: "What is that?"

"Rebibbia," he said.

I had heard of it, Rebibbia, where the hardcore criminals were sent. We turned into the prison complex and pulled up to a building with a silver steel garage door that reminded me of something I'd seen in a James Bond movie. The door went up and we drove into a concrete loading area. The handcuffs were removed and I was escorted to a room, photographed and fingerprinted. After that I was escorted to a hall and fell in line behind the other fools who had been arrested that night, a motley crew of 20 men. No sign of Pappas.

I was thinking about what my mother had said before I left the country. We were standing on the driveway, getting ready to go to the airport. "Peter, please don't get in trouble."

I said: "What do you think I'm going to do?"

The line kept moving, and when it was my turn I stepped up to the open half-door of a storeroom and was given a stained towel, a bar of soap and a distressed cup made out of extruded metal. A guard escorted me to a cell, solitary confinement, which seemed like a blessing under the circumstances. It was now 4.30 in the morning. I was exhausted and fell asleep fast.

Next thing I remember, I was in that state between sleep and waking up when your mind can play tricks on you. I was thinking about the events of the previous night, wondering if it was a dream, and then I opened my eyes and saw the morning sunlight coming through the barred window creating a distorted pattern on the tile floor. The room had a bed, an orange metal frame bolted to the wall and a stained mattress, a toilet, and scarred, graffiti-covered walls. A guy named Ricki professing his love for Ana.

On my second day in captivity a woman from the American embassy visited and gave me a couple packs of Marlboros and two Hershey bars. I said: "Do you have any news from Father Felice?" He was the director of the university. She didn't know who he was, which wasn't a good sign. I hadn't heard anything from Felice or anyone else, and I was starting to wonder. Except for an hour in the exercise yard each day, I was locked in the 6ft x 8ft cell and I was getting anxious,

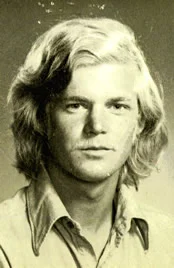

The exercise yard, with its concrete floor and chain-link walls, looked like it had been lifted from the projects in Detroit. I would stand with my back to the fence, feeling the warmth of the sun. Inmates would come up and ask if I was Swedish. When I told them I was an American they assumed I had been arrested for drugs. "No," I would say, "stealing a taxi." And the typical response would be: "That's not bad. You get eight months, maybe a year, but no more than that." Hearing it freaked me out. I thought: eight months – I've got to get out of here.

One afternoon in the yard a dark-skinned guy, who looked Tunisian or Moroccan, tried to take my cigarettes. I didn't say anything, just stepped in and hit him in the face, and he went down. No one else bothered me after that.

Early in the morning of day four I was taken to a holding cell, where I met my court-appointed attorney, a young guy named Sergio who didn't speak English. I asked him to contact Father Felice and find out was going on, but I don't think he understood. Sergio represented me during the arraignment that was held in a conference room at the prison. A judge advocate explained the charges against me and said I would be going to trial in a few days.

After the arraignment, I was moved to a four-man cell in general population. Pappas had been moved there, too. Our cellmates were Alejo, a 25-year-old pickpocket from Buenos Aires, and Spoleto, a 72-year-old armed robber who had been incarcerated since Mussolini was in power. Spoleto was demented and slept in his clothes, thinking he was going to be released any minute.

I spent the next three days reading crime fiction from the prison library, and thinking some day I would use the Rebibbia experience in a novel. On day seven I was escorted to a large holding cell filled with prisoners, most of whom were throwing salt over their left shoulder for good luck before going to court. Pappas appeared a little later handcuffed to a thin frightened Italian. I was handcuffed to a little Sardinian guy who might've been 5ft tall. When we rode on a bench seat in the back of a van, six of us on one side with our backs to six others, the Sardinian's little feet dangled above the floor.

In court we were represented by father/son attorneys hired by Father Felice. Here's what I remember: there were three judges and a prosecutor all wearing powdered wigs and black robes. The prosecutor shouted at us in a loud theatrical voice. Our attorneys answered the charges and the three judges spoke to each other in hushed tones. It was over in 10 minutes. I was acquitted; there was no evidence against me. Pappas was found guilty and fined 20,000 lire, about $34. We found out later that Pappas's attorney and one of the judges were friends and a deal had been made.

We were released, but it wasn't over. Guilty or not, we were given 48 hours to leave the country. Which coincided with the end of the school year and our flight back to Chicago. Pappas and I were in the airport drinking beer with our friends when two Carabinieri in swat fatigues called our names and escorted Signore Pappas and Signore Leonard out of the airport terminal, through a gate to the tarmac and up the stairway that led to our plane. We were officially kicked out of Italy, personae non gratae.

We arrived in Chicago the next morning and I took a connecting flight a few hours later. My father, Elmore Leonard, was waiting at the gate when I got off the plane in Detroit. Elmore looked at me and said: "Hard time makes the boy the man."