Boy You're On Your Way

I remember when I was nine years old, going down the stairs to the basement, seeing my dad at his desk, white cinder block wall behind him, concrete floor. He was writing longhand on unlined, 8½ x 11 yellow paper, typewriter on a metal stand next to his chair. Across the room was a red wicker waste basket, balls of yellow paper on the floor around it, scenes that didn’t work, pages that didn’t make it in the basket. In retrospect, it looked like a prison cell but my father didn’t seem conscious of his surroundings, deep in concentration, midway through a western called Hombre that would be made into a movie starring Paul Newman.

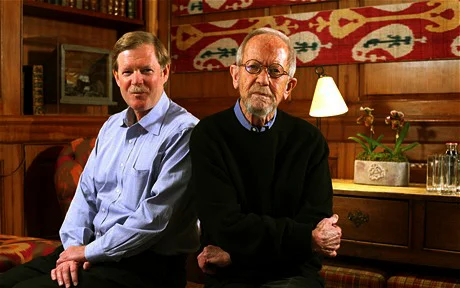

Forty years later I remember visiting my father after work one evening. I was stressed out after presenting a new ad campaign to Volkswagen that got lukewarm reception. Elmore no longer wrote in a cinder block basement. With forty novels and a dozen scripts to his credit, he now worked in the living room of his manor home in Bloomfield Hills, a tiny suburb of Detroit. What struck me was that his desk looked much the same as it had that day when I was nine. Same yellow pad, and half a dozen balls of yellow paper next to the waste basket against the wall, electric typewriter on a metal stand behind the desk. No computer anywhere in sight. Elmore in Levis and sandals and a dark blue Nine Inch Nails T-shirt, talking enthusiastically about the opening scene of his new book called The Hot Kid.

Watching my father, I thought, here’s a guy who really loves what he’s doing, and I didn’t. Earlier that afternoon, during my presentation, the VW ad manager had taken my first campaign board and flung it like a frisbee across the conference room. And I thought that was our best idea.

I don’t know if my observations that day were the final motivator, or if it was my continued disinterest in advertising, but a couple months later I decided to write a novel. I was forty nine. I remember sitting on a couch in the family room, writing the opening scene of a book called Invasion, while two of my kids, Alex and Max, were doing their homework. I read what I had written and thought: this isn’t bad, maybe I can do it.

The last piece of fiction I had written was in 1974. I had taken a creative writing class my senior year in college and really enjoyed it. I never aspired to be a novelist, but after graduating I wrote a six page short story—I can’t remember the title—and mailed it to my father to see what he thought. A few days later I received his three page critique. One line summed up his point of view. “Your characters are like strips of leather drying in the sun. They all look and sound the same.” That from a writer who never used similes or metaphors.

I had not written another word of fiction in twenty five years. But as I looked back, it had less to do with Elmore’s comments and more to do with getting a job and getting married and raising kids and starting a business. I may also have been intimidated because my father was so good. In fact, I remember having dinner with Senator Don Riegel—he lived in the neighborhood and our daughters were friends. I told Don I was writing a book and he said, “You writing a book is like Michael Jordon’s son trying out for the NBA.”

I said, “Don, thanks for your support.”

He said, “No, I was kidding. I’m sure you’ll make it.’”

It took a year and a half to finish Invasion. I didn’t want Elmore involved in any way, so he suggested sending it to Jackie Farber, his former editor at Delacourt.

He said, “Jackie’s good. She’ll tell you the truth.”

I was excited. I thought it was a good story with good characters. I mailed the three hundred page manuscript to Jackie and called her a week later. I said, “What’d you think?”

“You’ve got a nice facile style,” Jackie said. “But I have one question. Who’s your protagonist?”

I knew who the main character was, but if it wasn’t obvious, I had a problem. I was disappointed, but I could understand what Jackie was saying. I had thirty seven characters, and a murky plot that needed thinning out. I didn’t try to defend the book. I put it aside remembering the prophetic words of Russell Banks:

“Most novelists have a failed attempt or two, books that didn’t work, didn’t make it. Pages in a desk drawer somewhere.”

I didn’t dwell on the failure of my first novel. I had another idea and began writing Quiver, a story about a woman whose husband is killed in a bow hunting accident by her sixteen-year-old son. While the main character, Kate McCall deals with the loss of her husband and her son’s surly guilt, her ex-con, ex-boyfriend comes back in her life and sets into motion a series of events culminating in a life or death confrontation with a gang of killers.

I sent Quiver to my agent, Jeff Posternak at the Wylie Agency. He read it and said, “I guarantee this is going to sell.”

And it did.

I remember when Jeff called with the good news. It was an overcast day in March. I was in my office, looking out the window, trying to think of a headline for an ad. The phone rang and I saw the New York caller ID. I picked it up and said, “hello.”

Jeff said, “I’ve got good news for you. Are you sitting down? You’re going to be published. St. Martin’s has made an offer for two books.”

I can’t tell you how elated I was, finally breaking through after three and a half years. It’s a real kick to hold your first published book in your hands, and then to see it on a shelf in bookstores. I don’t think that’ll ever get old. I called my father and told him.

He said, “Boy, you’re on your way.”